I began my career as a teacher in the early 2000s, at the ripe age of 21, ready to take on the world. I taught 11th grade English at a New England boarding school, eager to make a difference in the lives of my students by teaching them to read with rigor and write with conviction. I was proud of my chosen career path, serving the greater good. I congratulated myself on avoiding the corporate grind and not succumbing to working for “the man.”

My ire quickly ignited, however, when I started hearing stories of the school’s CFO. I envisioned him as a mustache-twisting Disney villain, scheming to line his pockets with school profits generated at the expense of faculty and students. He would send emails asking employees to conserve energy or decrease our use of disposables in the dining room. The gall! Penny-pinching at every opportunity, it became clear to me that “the man” was once again present in my new career.

Fast forward to 2023, where I am now an eight-year veteran of the business office. And that nefarious CFO? Well, that was Tom Sides of The Kent School who, in addition to being one of the kindest human beings you will ever meet, may very well be on the Mount Rushmore of independent school CFOs. But none of that mattered to 21-year-old me — Tom Sides was a menace who needed to be stopped.

Perhaps my distrust of the business office was misguided and unique to me, but it highlights a chasm that exists between many business offices and their school’s faculty. I was a teacher who didn’t understand business, didn’t want to understand business, and actively chose a career to ensure I would not need to understand business. There was no way that I, as a faculty member, was going to build that bridge to the business arm of my school; that connection needed to be initiated from the business office.

There are many ways for business officers to build that bridge, but there is no substitute for walking a mile in the shoes of the faculty. For that reason, I cannot think of any better way for a business officer to connect with their faculty, students and mission than to teach.

I know several business officers around the country who have jumped into the classroom at their respective schools to better empathize with their faculty. “I think because I teach, I have far more credibility among the faculty,” said Julia Gabriele, who is CFO at St. Luke’s School in New Canaan, Connecticut, and teaches an Epicurean literature course. “In addition, it gives me an important teacher perspective when building a budget each year.” Pam MacAffer, assistant head for finance and operations at Rye Country Day School, would agree: “The school schedule is an important topic at most schools, and teaching economics allows me to live the schedule from a teacher’s perspective.”

Perhaps even more important than the connection with faculty is the connection with students. “It’s all about the kids,” said Sam Goldfischer, CFO at Newark Academy, who has taught economics, personal finance and Holocaust studies over many years. “Getting into the classroom has always been the best part of my day.” Philicia Levinson, CFO at the Morristown-Beard School, reported that “teaching my quantitative business analysis course has unquestionably made me a better business officer because it keeps me connected to the students and sensitive to the needs of faculty.” Chance Van Sciver, CFO at Doane Academy, teaches a junior seminar for budgeting after college, and is also the head coach of the varsity crew team. “I know that teaching and coaching has made me a stronger leader at my school. It’s the best way I know to stay connected to the mission, the students and the faculty.”

There are many low-risk ways to tread lightly into the waters of academic program before taking on a classroom of students. Business officers might co-lead a student investment club or serve as an assistant coach for an athletic team. Contributing to a summer or auxiliary program might offer a less intrusive schedule. Something as simple as running the scoreboard for home basketball games could be a way to get involved.

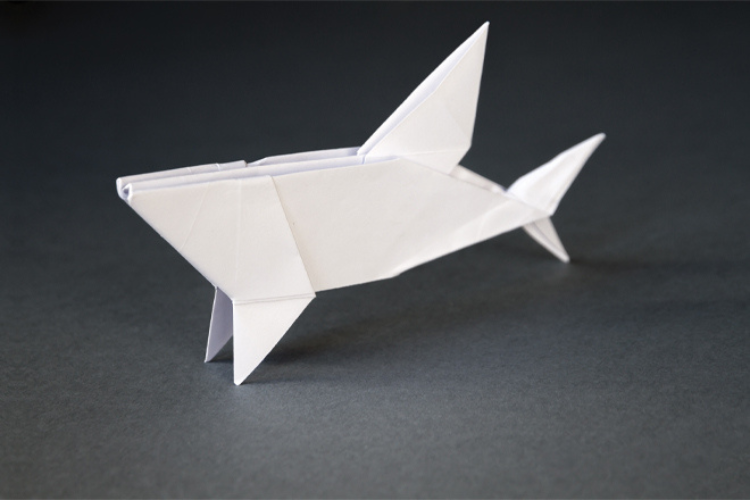

Nothing says “I see you” to a tired faculty member like trying to wrangle a group of 12-year-olds who can smell summer vacation around the corner. I wear a lot of hats in my role as a school administrator, but “Shark Tank teacher” is one I am incredibly proud of.

For me, my re-entry to the classroom was through teaching a week-long “Shark Tank” summer camp class to fifth and sixth graders, which covered the basics of entrepreneurship. The students would come up with a business idea, build a business plan throughout the week, and pitch their idea to a panel of “sharks” (made up of members of the school’s finance committee). It was an incredibly fun, rewarding and admittedly tiring experience. Even in only a week’s time, I was able to build genuine relationships with students that I simply would not have the opportunity to interact with during a normal day at the office. And nothing says “I see you” to a tired faculty member like trying to wrangle a group of 12-year-olds who can smell summer vacation around the corner. I wear a lot of hats in my role as a school administrator, but “Shark Tank teacher” is one I am incredibly proud of.

At this year’s NBOA Annual Meeting in Los Angeles, when accepting the Ken White Distinguished Business Officer Award, Chuck McCullagh asked the audience an important question: “Why do we do what we do?” The “what” we do as business officers can look similar across schools — finance, accounting, operations, human resources, food service and risk management, among many other responsibilities. But the “why” says a lot more about who we are as people. If you’ve ever struggled to answer Chuck’s question for yourself, you might ask, What do others at my school do? There is no better way to understand what they do than to jump in and try one of many ways of teaching. It might not be easy, and the students will no doubt tire you out, but you most certainly will have an answer to the question, “Why do we do what we do?”