Article by Deborah Synder, Marin Montessori School

One Sunday in 2004, I was reading the San Francisco Chronicle, and the lead article in the travel section described a 192-mile coast-to-coast walk across England. The article described going from pub to pub, hiking out in the wide-open country — elements of a unique and different vacation. But 192 miles in 17 days? Could I do that? I filed away the newspaper clipping to think about later. Then, as it happens, life got in the way: babies, divorces, new jobs, taking on the position of director of finance for my school. The idea of such a long and remote vacation faded into the background.

That is until 2015, when my husband and I decided to “take a hike,” so to speak. We booked the flight from San Francisco to Manchester, England, arranged for a company to transport our luggage from inn to inn, and started getting into shape.

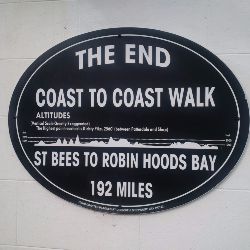

The hike we had chosen was Alfred Wainwrights’ coast-to-coast walk, an unofficial footpath named for the “fellwalker” who devised it and wrote the accompanying guidebook. “The Walk,” as Brits are inclined to call it, starts in St. Bee’s Bay on the western-most side of Northern England. The route then wanders across the country, to arrive 192 miles later in Robin Hood's Bay, also in the North. Following an age-old tradition of dipping your toes in the Irish Sea on one side and then in the North Sea on the other had a charm and attraction — there are so few places you can go from one coast to the other, and that’s what appealed to us.

To prepare, we haunted the local REI store, procuring boots, Camelback day packs, fleece vests, waterproof rain gear and whistles in case of emergency. We tried out different GPS units, power bars and technologies to keep us in touch with folks back home. But despite training every weekend in our boots and backpacks around the hills near our home in Novato, California, the physical demands of the trip came as a shock.

Our first day was 18.4 miles. In all of our training, we had never hiked that far, and that was only day one. Part of the problem was our GPS, which we were still getting used to, plus the notoriously unmarked trails. The second day, when I was already tired and still jetlagged, was the worst hiking day of my life: We faced an elevation gain of 2,567 feet of big stone steps in gale-force winds and pelting rain. Petrified that I would fall, get badly hurt and end up stranded, we trudged along another double-digit mileage day. At dinner that evening, I told my husband, “Call United Airlines. I’m going home.”

But after a glass of wine and a good night’s sleep, we decided that we would do what we could. One thing that pulled me along were the other hikers we met on the trail. Because a great part of the trail is unmarked, we relied on the guidebook, maps from the tour company, GPS and fellow trekkers to get from one point to the next. There was a family with red jackets that we’d usually see three or four ridges away, and we would set our sights on that ridge. My standard attire included a watermelon pink rain slicker, and people said they could see me from a distance too. The slicker came in handy because it rained every single day.

In walking 192 miles, you see many things. We walked by the town where James Herriot’s “All Creatures Great and Small” practice was. We walked through hundreds of sheep pastures and by thousands of sheep. I can’t tell you how much we talked about sheep. Black sheep, white sheep, shaggy sheep, high country sheep, young sheep, old sheep. No wonder that part of the country exports so many wool products.

As luck would have it, when we were traversing an especially remote part of the trail, I got word that a multi-million dollar land sale that my school had been working on for months was ready to close. I had planned to settle the transaction well after I returned, but plans change, and I was able to manage the escrow with very little internet and a 12-hour time difference. That’s what business officers do, yes?

I came to realize that the trek was not unlike working in the business office. On the hike, we’d wake up every morning with our map and list and supplies, and then by midday that plan might fall apart, but we’d pull it together, and at the end of the day there was dinner — often fish and chips or something equally British. In the business office, one has plans and an agenda and then school happens. We have to be able to remain confident and focused when we have crises at our school and keep going.

Midway through the last day of the hike, which was 22 miles, one of my feet sunk into a bog. Bogs hide; you often can’t see them. The ground felt solid when I poked it with my stick, but I sunk nearly up to my thigh. The muck almost sucked off my boot! Somehow I leapfrogged out of that hole. As I was pouring bog water out of my boots, knowing I would have to walk another five miles with wet socks, I thought: That’s just a business officer getting through it.

Deborah Snyder is director of finance at Marin Montessori School, an AMI Montessori school for toddlers through 9th grade in Corte Madera, California. For more on her adventure, visit her blog.

Photos courtesy of Synder.

Download a PDF of the article.

.png?sfvrsn=e0147111_1)