Article by James Pugh, James Pugh & Associates, Ed Biddle, The Masters School, and Robert Sedivy

The following is an excerpt of the article "Recession and Pandemic: How the Events of 2008 and 2009 Affected Independent Schools." Find the full version here.

The COVID-19 crisis has put nearly every aspect of the independent school to the test. Not since the financial crisis of 2008-2009 have crisis response plans, business continuity, cash flow, scenario planning and school leadership come under such intense pressure.

Since the onset of the pandemic in the United States, independent school leaders moved quickly to react in the short term to minimize long-term damage as they adapt to the new normal. Joining in on this task, we prepared an analysis which uses the data of independent schools from the early days of NBOA’s Financial Position Survey for FY 2008, 2009, and 2010. We also evaluated findings from BIIS FY 2019 and 2020 data collection, and incorporated information from recent NAIS Snapshot surveys. An economic downturn is of course different from a health crisis. The range of responses to the two situations gives perspective and offers lessons about the ever-increasing complexity of managing an independent school.

In contrast to the underlying financial cause of the 2008 recession, the current crisis is rooted in a health crisis that has caused far-reaching and unexpected financial repercussions.

We also evaluated findings from the NBOA Business Intelligence for Independent Schools (BIIS) 2019-20 data collection. Our consolidated findings show that the pandemic-driven crisis differs sharply from other recent economic downturns for independent schools. In contrast to the underlying financial cause of the 2008 recession, the current crisis is rooted in a health crisis that has caused far-reaching and unexpected financial repercussions.

Drawing lessons from the earlier crisis and from what we have already learned from the responses to COVID-19, as well as our interviews with current heads of schools, two primary areas of importance emerge:

- Acting with flexibility: The pandemic has been a moving target. Some schools’ responses worked and were retained. Others were discarded as scientific understanding of the virus, its transmission and its possible containment evolved.

- Preparing for shifting work and school arrangements: Post-pandemic, business continuity plans will need to include teachers, staff and programs as well as cash positions and liquidity. Never has the need for a deep bench been more apparent in the governance, administration and staffing of our schools.

Lessons From the 2008-09 Financial Crisis

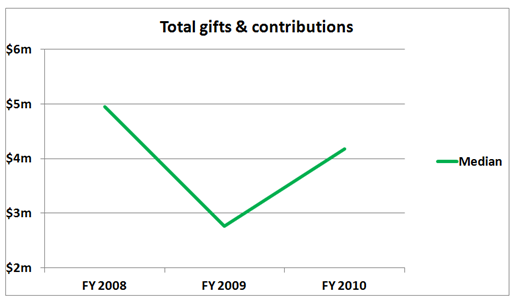

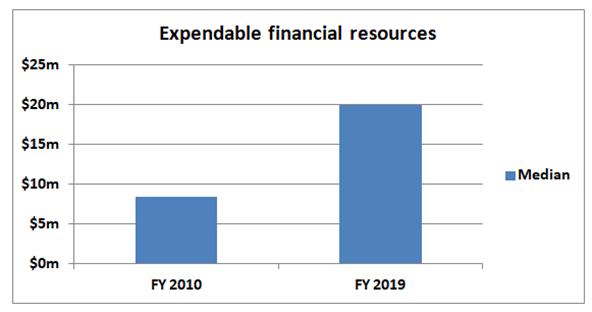

During the Great Recession, independent schools, particularly those with larger endowments, saw an immediate impact on expendable financial resources (EFR). Our analysis of independent schools during this period shows that EFR fell by 28% in fiscal year 2009. Contributions fell by 44% in FY 2009 from a median of $5.0 million to $2.8 million. The median operating margin fell from 4.9% in FY 2008 to 0.0% (break-even) in FY 2009.

Cost reduction, both immediate and planned, was the predominant response among independent schools. The planning process often started with a conversation between the board chair and the head of school to identify the “non-negotiables,” or the core attributes of the school that needed to be preserved at all costs.

Boards of trustees directed administrations to reduce costs by a certain amount and within a certain time frame. This led to school-wide discussions with department heads about delivering programs more cost effectively, and by deferring or eliminating discretionary expenses. This was a top-down process that needed input from across the organization.

The most dramatic impact was felt by schools that had big projects planned. Some postponed launching capital campaigns while others put off constructing new buildings.

Some faculty and staff who had been planning on retirement decided to continue working as they saw their retirement savings decline. In fact, a teacher attrition survey conducted by James Pugh in years 2001, 2002, 2003 and 2009 shows that the retirement or departures of teachers aged 60 and above dropped 30% in 2009. Schools planning on saving from the retirement of more highly paid employees instead saw the expense continuing.

The most dramatic impact was felt by schools that had big projects planned. Some postponed launching capital campaigns while others put off constructing new buildings. Capital spending fell by 34% in FY 2009; it fell by another 26% in FY 2010. Schools that were on a growth trajectory had to rethink their long-range plans.

Yet the sky did not fall in FY 2009 or FY 2010. Enrollment held steady, in part, because schools increased their financial aid. The median tuition discount rate increased from 18.0% in FY 2008 to 18.7% in FY 2009. In FY 2010, it jumped to 21.1%.

About 50% of a surveyed group of schools across the country reduced their operating expenses in FY 2010. This allowed operating budgets to stabilize. The median operating margin increased slightly to 0.3% in FY 2010.

We also saw the median of contributions in FY 2010 increase to 85% of FY 2008 levels. The median of expendable financial resources (EFR) in FY 2010 increased to 90% of FY 2008 levels.

There were other, less tangible, responses. Some schools were more flexible in releasing parents from contracts, hoping they would return after the economy stabilized. Investment strategies were modified at some schools to be more conservative. The search for alternative sources of revenue from auxiliary programs or supplemental educational programs gained momentum. Many schools froze pay rates and some cut back on retirement plan funding and other benefits.

While sometimes intended as a short-term accommodation, increases in financial aid are difficult to work out of the admissions and enrollment fabric once awarded.

The additional financial aid awarded on the heels of the recession generally stuck. While sometimes intended as a short-term accommodation, increases in financial aid are difficult to work out of the admissions and enrollment fabric once awarded.

Most schools were nimble enough to avoid lasting damage from the 2008 recession, and the economy bounced back. In FY 2010 median contributions increased to 85% of its FY 2008 level. Also in FY 2010 the median of EFR increased to 90% of its FY 2008 level.

This ensured that schools would be better prepared for the next hiccup in the economy. For a year or more, the Great Recession appeared to reduce the ability of families to afford an independent school. The finances of schools and their programs were threatened. The situation was reasonably well-defined and well-understood from the start. Cutting low-priority costs, finding operating efficiencies and flexible responses to parents’ financial problems were necessary to keep schools operating through the economic trough. The budget levers were driven by the finance committee, the head of school and the chief financial officer.

Lessons From the COVID-19 Pandemic

At the same time, schools faced pressure from families regarding additional financial aid, tuition refunds and/or uncollectable tuition. As a result, the playbook for the annual budget process was largely ignored.

The pandemic, unlike the Great Recession, presented a moving target for school leaders. For example, according the NAIS Snapshot surveys, in September 2020, 47% of schools opened with fully in-person teaching, 24% operated completely by remote learning, and 29% used a hybrid mix. Four months later, in January 2021, just 14% of schools were teaching only remotely. Among schools responding to the May 2021 Snapshot survey, none were using only distance-learning. 83% were using only in-person learning, and 17% were using a hybrid model.

On the financial front, many schools initially spent the equivalent of 5% or more of their budget (including capital) on items that addressed pandemic-related issues in order to open their campuses in fall 2020. Expenses included technology upgrades, additional furniture, tents and trailers, as well as additional staff and teaching aides. At the same time, schools faced pressure from families regarding additional financial aid, tuition refunds and/or uncollectable tuition. As a result, the playbook for the annual budget process was largely ignored.

However, there was limited overall impact on school finances in the early stages of the pandemic. The most recent data in the NBOA BIIS platform shows the median operating income increased by 3.5% in FY 2020, while median operating expenses decreased by 0.5%. As a result, the median operating margin increased from 1.7% in FY 2019 to 2.4%. There were cost savings from shifting to remote operations that largely offset the costs of added support staff and the initial outfitting of facilities to re-open safely.

Some independent schools saw enrollment go up, as parents increasingly sought schools that were fully in-person rather than remote. For many, that meant switching to an independent school, regardless of the price tag. At the same time, however, some urban independent schools found enrollment declining as parents who could work remotely moved to a suburban or rural setting. An increased interest in boarding schools appears in part to be another form of student dispersal. It remains to be seen whether the demographic shift away from urban centers will be a lasting change.

Unlike the recession, many parents were able to work from home and maintain, more or less, the same level of pay and benefits. They had less cost for commuting and less expense for vacation trips as travel was curtailed. Some schools were even able to raise additional funds from donors specifically for COVID-19 response expense and for financial aid.

The federal government’s unprecedented fiscal interventions were also fairly successful. Government aid in the form of Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans assisted many independent schools. Schools that had never accepted any federal assistance revisited their policies. That said, initial findings from BIIS 2019-20 data collection also revealed that accounting for PPP loans was inconsistent. Some schools recorded the assistance as a loan to be repaid; others recorded it as a grant. Some schools declined the offer of PPP aid for a variety of reasons.

The pandemic has taught schools to think as broadly as possible in planning for emergencies and disasters. Business continuity planning needs to include the teachers, staff and program as well as cash position and liquidity. Emergency supply reserves should include protective equipment and cleaning supplies. Plans for sheltering in place based on everyone crowding into the strongest portions of buildings should be evaluated to include alternatives.

A recurring theme is the need for flexibility. One head of school commented, “Flexibility is key. Rigid, set-piece thinkers struggled and sometimes broke under the strain.”

Jim Pugh has served as CFO and history instructor at independent schools in the East and the Midwest for the last five decades. He currently conducts surveys for a half-dozen regional groups and associations. He lives in Cornwall, Vermont.

Robert Sedivy retired in 2008, after 20 years as CFO of a large K-12 day school. His prior experience was in colleges and a museum. He now teaches and consults on independent school management and finance. He lives in Bloomfield, Connecticut.

Ed Biddle is the CFO of the Masters School in Dobbs Ferry, New York. He retired from JP Morgan Chase in 2015 where he served as a managing director. He worked at that firm for 27 years. He lives in Katonah, New York.