Article by Cecily Garber

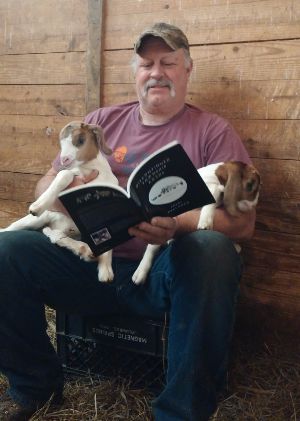

Photo above: "Farmer Joe" Heathcock of Sandy Spring Friends teaches students about sustainable agriculture.

Nestled among a barn and other red-painted farm buildings, the Grange at The Hotchkiss School, in Lakeville, Connecticut, looks unassuming, with an unfinished cedar exterior and metal roof. But it’s a busy facility. Part food-processing center, part classroom and part reception hall, the $1.35 million building is unlike any other structure on campus. It sits at the edge of Fairfield Farm, on land that the school purchased in 2004 and that now yields 23,000 pounds of organic produce each year.

Why would an independent school without a history of farming make these investments? Hotchkiss does save $150,000 annually on beef production, raising its own herd. But produce raised organically by students costs more than buying it outright. Simply put, environmental initiatives are a central element of the Hotchkiss value proposition. The farm is featured alongside faculty, student life, the arts and athletics on its “about” webpage, for example. Moreover, students, faculty and staff benefit from the Grange and land around it in manifold ways. “Our primary goal is not cost savings, but education,” clarified Joshua Hahn, assistant head of school and director of environmental initiatives. “We see the facility more in line with the hockey rink or the music hall — a venue for education,” added CFO John Tuke. “The farm is just another ‘classroom,’ albeit a very large and natural one.”

One of the goals of the Grange is to break down the barrier between food service staff and students. We wanted...to teach students that knowledge does not always come from a classroom or faculty member.

Joshua Hahn

The Hotchkiss School

The Grange plays host to events that range from beet-washing and biology class to the senior dance and trustee dinners. As for the farm, it provides 32 percent of the school’s produce over the academic year and 95 percent of the beef. Two-thirds of all academic classes had visited the farm or the Grange by April of the 2016-17 school year; about 25 students a year work on the farm after school as their “sport” during the fall and spring seasons; and over the summer, students from Hotchkiss and other local schools complete farming internships.

By integrating food service operations with academic and extracurricular offerings, Hotchkiss offers its students a different kind of learning opportunity. “One of the goals of the Grange is to break down the barrier between food service staff and students,” explained Hahn. “We wanted students in the kitchen, not being served by people ‘behind the line,’ to teach students that knowledge does not always come from a classroom or faculty member.”

Nationwide, growing numbers of independent schools — rural, suburban and urban — are implementing farm-to-table programs. Here’s a look at four.

Founding a Farm: The Hotchkiss School

The Hotchkiss School has been surrounded by agriculture and rural beauty since its founding in 1891, but it wasn’t until 2004 that the school bought the 200-plus acres that would become Fairfield Farm. Special draws from the endowment funded the purchase, and savings in other budgets seeded the initial operating costs, according to Tuke. However, “Most of the growth of the farm program has come through new gifts to the school, many of which have been from people who had not given at high levels in the past,” said Hahn. The school raised $2.7 million to endow the Grange and a new barn as well as two related staff roles, farm manager and farm curriculum coordinator.

Summer and early fall are New England’s high growing season, and when the farm began yielding large amounts of produce, Hotchkiss needed a place to store its bounty over the course of the year. From humble beginnings — desire for an old-fashioned root cellar, plus bathrooms and a farm manager’s office — the Grange was born. Completed in 2015, the 6,000-square-foot building today features an oversized porch, commercial kitchen with large seminar-style table, vegetable cleaning facilities, dry storage, office and shower. Below ground are one dry and two cold storage rooms covered by an insulated floor and kept cool by the surrounding earth. Rooftop solar panels provide most of the electric power.

Fairfield Farm at The Hotchkiss School

Meeting the needs of an organic farm as well as corporate standards for food sanitation and preservation in one building was a challenge. “We had to combine a ‘crunchy granola’ program with national level requirements,” said Daniela Holt Voith of Voith & MacTavish architects, which designed the building. In this quest, the firm worked with national food suppliers that provide the food Fairfield Farm and local growers cannot produce, as well as with neighboring farmers who shared agricultural expertise and even equipment in the farm’s early days.

“The school has committed to the farm as a primary vehicle for teaching about the environment and demonstrated to students that we, as an institution, grapple with the same issues we teach about,” said Hahn. “With that in mind, we have invested appropriate resources in the program, as we have in arts, athletics and other areas of school life we feel are critical to developing our students.”

Going Organic: Olney Friends School

Unlike Hotchkiss, Olney Friends School in Barnesville, Ohio, has been closely connected to agriculture since its founding, by farmers, in 1837. A boarding school of about 50 high school students, it owns 350 acres of farmland. However, its use of that acreage has changed dramatically over the years, especially recently. From 1956 until 2007, Olney Friends cared for a registered Jersey cattle herd that supplied all the school’s milk. In 2007, the school sold the cows and shifted back to growing produce and raising livestock for the school’s food supply. “Growing our own food just makes sense,” said Kristal McGee, business manager. “Organic farming starts with nourishing the soil, the plants and eventually our bodies.”

The benefits of producing our own food far outweigh the costs.

Kristal McGee

Olney Friends School

To make the change, Olney Friends invested in numerous projects. For instance, it built a vegetable processing center using repurposed materials; acquired cold storage and freezer space for bulk harvesting; revived an out-of-commission greenhouse; upgraded its beef handling facilities; and built a new hoop house for seedlings, two chicken houses and a hay barn. In 2014, the school applied for organic certification and received it within a year — two years faster than average — thanks to meticulous record-keeping.

While the beef, chicken, eggs and produce “reduce the kitchen food provisions budget drastically during the growing season, the costs of operating the farm are higher due to adhering to organic certification standards,” said McGee. “But it’s worth it. The benefits of producing our own food far outweigh the costs.”

Shortly after the farm began transitioning to organic standards, “the farm team” formed as an alternative to traditional sports. Since then, the farm has become more integrated into the high school curriculum. Students not only learn how to compost and test the soil but study genetics and statistics hands-on. They tend and harvest crops. Some monitor goats and hens as the animals prepare to give birth. Others mend fences and build trails. Still others serve as ambassadors on FARmOUT day, a two-day event that teaches local middle school students about food production. Alumni and local community members also donate volunteer hours to the farm. “We couldn’t do it without their help,” McGee added.

Most importantly, the farm enables Olney Friends to better carry out its mission. “The farm represents to us the Quaker ‘SPICES’: simplicity, peace, integrity, community, equality and especially stewardship,” explained McGee. And it attracts students from urban families that haven’t had much exposure to rural areas. “The idea that a student can get a top-notch college preparatory education and hands-on learning is appealing to many… We’re not trying to produce farmers here, but we are producing informed decision-makers.”

Urban Oasis: Near North Montessori School

Just three miles northwest of Chicago’s Grant Park, Near North Montessori School’s urban campus doesn’t span acres of land. But “the Farmessori,” on a large plot a few blocks away from the main building, still produces eggs, honey, fruits, vegetables and herbs. With that bounty, the school’s junior high students plan, produce and distribute 100 to 150 made-to-order lunches a week, sold to students, faculty and staff in the school’s Sandwich Shoppe.

More than 20 years ago, the 580-student infant through grade 8 day school launched the Sandwich Shoppe lunch program to realize its founder’s belief that adolescents should practice economic independence. Initially, the operation focused primarily on business rather than farm-to-table practices, and food preparation was minimal. In 2009, NNM built a warming kitchen near its junior high classes, which led to more student food preparation. Three years later, the farm-to-table commitment took off when the junior high curriculum shifted its focus to basic economics, entrepreneurship, mindful farming and active citizenship.

The honeybees of Near North Montessori (first of six videos)

NNM now has a city-certified commercial kitchen. It renovated the original warming kitchen over two years, at a cost of about $22,000. Investments included new sinks, commercial grade grills, burners and ovens, as well as a city-approved “home economics” curriculum and dedicated food manager. Students receive state-mandated food handler training and certification. Four full-time employees, some 10-month and others 12, support the program by managing the farm, coordinating farm-to-kitchen activities, working with elementary students and running the Sandwich Shoppe program. Over the summer, parent and student volunteers help harvest and store produce for the upcoming year.

The Sandwich Shoppe makes about $10,000 in profits every year. Students give $1,500 of those earnings to the rising class of operators as seed money. They donate the remainder to local partnership organizations.

Long-term maintenance is not a concern for NNM because the programs are so deeply embedded in the students’ lives. “Because both the Farmessori and Sandwich Shoppe exist to fulfill real community need, the students take the responsibility of maintaining the farm-to-table relationship seriously,” said Jamee Warrenfeltz, who teaches junior high economics and is coordinator of the Sandwich Shoppe. “There is no room for neglect.”

Furthermore, both programs are deeply entwined with the school’s mission. “At the heart of the farm-to-table program are cycles and connections that exist year-round and year-to-year,” Warrenfeltz said. “It’s an opportunity for students to be a part of something larger than themselves.”

The Farmessori has been one of the school’s best investments. It brings the whole community together... [and] our community is what differentiates us.

Linda Rudnick

Near North Montessori

Linda Rudnick, the school’s finance director, agrees. “The Farmessori has been one of the school’s best investments,” she said. “It brings the whole community together, from children (across all grade levels) to parents and then to our neighbors. Our community is what differentiates us — it’s so strong — and the Farmessori is a big part of that bond.”

Suburban Sustainability: Sandy Spring Friends School

Like many schools, Sandy Spring Friends started various gardens over the years that eventually went by the wayside. That changed when the 600-student, day/boarding preK-12 school in Sandy Spring, Maryland, hired a residential community farmer to work with dorm students, manage farming summer programs and grow vegetables for the cafeteria and a small school market.

Four years ago, Joe Heathcock (“Farmer Joe” to lower-school students) took that position and expanded it. He applied for grants, including one from the county government to improve storm water management and restore natural habitat. To better control runoff from impermeable surfaces such as roofs and parking lots, Heathcock and students built a rain garden, replaced gutters with cisterns to collect rain water and planted mushrooms around the campus lake to absorb harmful bacteria, reducing the chemicals needed to keep the lake clean. A smaller grant from the Whole Kids Foundation provided funding for classroom tools to make seedling boxes.

The single-acre vegetable patch has expanded into an 11-acre permaculture orchard, which draws on principles of natural ecosystems to create sustainable agriculture. Heathcock arranged a lease of 10 acres adjacent to the school and built a fence around them — the most expensive investment after labor — to keep the robust deer population at bay. The lower, middle and upper school each dedicated a full day to planting the new land with perennial trees. “The middle school kids were talking about their grandchildren eating chestnuts off those trees,” said Heathcock. “That was priceless.”

Heathcock’s work has expanded into the classroom too. For instance, he helped a high school student design a biology experiment to test the effectiveness of mushrooms in degrading diesel fuel. When teachers see the need for agricultural expertise, he works with classes as well as with individual students.

The admissions office has told me they’ve gotten lots of positive feedback about the farm program. It’s a distinctive asset.

Joe Heathcock

Sandy Spring Friends School

Sandy Spring Friends now employs a part-time farm employee in addition to Heathcock to help out with the agricultural work. This approach has proven more efficient than the student internships of the past, but a willing school community remains important. “Sometimes you have to harvest a crop of lettuce in the rain or feed the ducks day after summer day,” he said. Without students’ and campers’ help, the farm wouldn’t run at the scale it does.

The farm at Sandy Spring Friends touches one other all-important function: It’s a selling point to prospective families, Heathcock said. At the annual open house, he sets up a display of what’s grown on campus and answers questions about the cafeteria program and beyond. “The admissions office has told me they’ve gotten lots of positive feedback about the farm program. It’s a distinctive asset.”

Download a PDF of the article.

Read more about independent school facilities on NetAssets.org.