Article by Leah Thayer

Every independent school is unique, but not every school excels in the long game of incubating, financing and articulating its unique story. Seasons pass, markets shift. The economy may stumble, weakening the will or capacity to invest in the campus and programs. For any number of reasons, a school that once seemed solid can find itself on shaky ground.

What does it take to overcome difficult circumstances and thrive in trying times? Here’s a look at two very different but equally effective independent school leaders who, through clarity of mission and strategic financial stewardship, are at once honoring their schools’ roots and embracing the future. “It’s sort of a symbol of strength to tell that story now,” said one.

Under Pressure

When Mike Saxenian was interviewing for the head of school position at McLean School, he saw “a terrific product, a really talented faculty and a long tradition of service to students who learn differently,” but also a student population that had shrunk by nearly a third in five years. Declining enrollment was hardly unusual. It was 2013, and after 12 years as CFO and assistant head of school at Sidwell Friends, a larger and better known preK– 12 school in the Washington, D.C., market, he had witnessed many independent schools struggle through the recession, and had seen some respond by adding learning services to appeal to a broader market.

Saxenian believed McLean was different from these schools. As both a parent and administrator, he knew that none had the “comprehensive set of tools that McLean had,” he said. The school had always catered to bright students with mild to moderate learning differences — dyslexia, ADHD, anxiety, executive functioning. An added distinction was its college-prep curriculum and record of sending graduates to competitive colleges and universities. “There’s a big difference between adding a few learning specialists to support students outside of class, and what McLean had been doing for 60 years, which was creating a learning environment where the actual classroom setting engages them,” he said. “McLean had a much deeper and more powerful approach to serving bright students who learn in a different way.”

What McLean didn’t have was clarity beyond its core community about what it did so well. People seemed vaguely familiar with the school, but “it was almost like they had all gotten the same memo,” Saxenian said. “They would say, ‘It’s a great school… But I’m not sure what it’s doing.’” Some people thought it was a special-education school; others confused it with neighboring independent schools. Muddying the waters further was its location — McLean School is in Potomac, Maryland — across the river from The Potomac School, an independent K–12 school in McLean, Virginia. “There was some confusion about that,” said Saxenian.

Collectively, Saxenian’s impression of McLean was of “a shrinking student population, a lot of unmet need in the market and a great product. When I put those together it seemed clear that a piece of what had to happen was that we needed to do a better job of explaining what we did so well. In business terms, we needed to do a better job of marketing the school.”

Nearly 350 miles south, in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, Summit School had hooked Michael Ebeling from his first visit to its campus. “It was so clear to me that this school had a soul,” he said. “I had never experienced anything like it. Everything felt connected. The spaces were designed for children. The faculty were focused on children. The administration supported the faculty. Parents were supported as partners.” It was early summer 2008, and Ebeling had taken the position after serving as lower school director of a sister independent school for the previous eight years. “I thought naively I was going to come here and help build the program,” he said.

The stock market had other plans, of course, and three months after Ebeling’s first day, Winston-Salem and Summit School felt the crash acutely. “We dropped 45 students that first year,” he said. Enrollment dropped further the next two years, to a low of 507 students. Some families chose to go to nearby public schools. But Ebeling refused to accept price tag alone as the reason, and he instinctively knew that expense cuts alone were not the path to financial sustainability. “In my opinion, many of the schools who said they were hemorrhaging students because the school cost too much — I think that’s a dodge. I think they were hemorrhaging because parents were saying, ‘What my kid is getting is not worth the check I’m stroking.’ Their appreciation for the schools got pressure-tested. The two years that followed were a referendum on more clearly aligning our mission with action — not just our school, but every school.”

True North

Ebeling credits several factors for Summit’s eventual revival, but above all the vision of Louise Futrell, which helped him crystallize the school’s moral imperative and value proposition.

I didn't have the luxury of easing my way in.

Michael Ebeling, on becoming head of school at Summit School three months before the stock market crash of 2008.

Futrell started Summit in 1933 at the behest of parents concerned about funding cuts to local public schools. “It was the Depression, and she was confronted with a situation not of her making,” Ebeling said. “She wanted to reinvigorate education by creating a progressive school that embodied the very things the public schools were eliminating,” such as active learning, individualized instruction and attention to the whole child. “The truth of the matter is that largely what I’ve done, as an outsider, is help reawaken all the constituents to the core identity of the school. The brilliance of the founder is that her principles were both timely and timeless, and by honoring those principles, you actually give a school a reach into the future.” By comparison, he said, when schools lose sight of their mission, and sometimes even when they change it, “they get lost. We have a true north that never changes.”

Being true to that vision wasn’t always easy, however. “I came in never having been a head of school, and I didn’t have the luxury of easing my way in,” given the stock market crash, Ebeling said. Faced with a dive in tuition income, he worked with the school’s director of finance and operations to identify positions that could be eliminated, while also reducing salaries by 4 percent and zeroing-out the retirement match. Spring of 2009 was most painful, when the school eliminated 11 positions. “People were not feeling the love for me. It was tough.” He lost 15 pounds that first year.

What kept morale from plummeting was disciplined, face-to-face internal messaging — and listening. “You want to make darn sure that whatever move you’re making, do your best to communicate that this is for the good of the community,” Ebeling said. In faculty meetings at the school, as well as small group gatherings in faculty homes, he sought to engage faculty in identifying what the Summit community most valued about the school — “the binding agents that bring them here.” From these conversations, in concert with some unique and collaborative branding work, came the school’s tagline, “Inspiring Learning,” along with “the six promises” of Summit School that have shaped many of the investments made since that time.

At Summit School, our goal for our students and ourselves is to think creatively, reason systematically and work collaboratively. And to that end, we make these premises.

- Scholarship at its best

- A fertile learning environment

- A sturdy confidence

- Intellectual independence

- State of the art facilities

- Educators who engage the whole child

To this day, “Anyone on campus can tell a story about any one of the six promises,” Ebeling said. “We are the unique expression of them in 2017.”

We're losing money. We need to spend on programs that signal strength.

Mike Saxenian, on becoming head of McLean School in 2013.

Saxenian’s quick actions at McLean School also supported the pedagogy, but more through the lens of strategic spending. “Having the finance background from another school gave me a set of tools to understand both the challenges and the opportunities,” he said. Besides the branding confusion, he saw classroom technologies that were five to 10 years old and gathering dust (many teachers didn’t know how to use them, or see reasons to). The tech team consisted of “one person sort of huddled away in the server room.” As enrollment declined, admissions had become somewhat lax, enrolling students outside the school’s sweet spot. Facilities were beginning to show their age; the credit freeze of 2008 had put the kibosh on the purchase of a new upper school. Furthermore, “Because of bond covenants, our debt-service ratio made it hard for the school to make needed investments in technology, facilities, human resources and marketing,” Saxenian said.

On the other hand, the school had solid financial reserves and net revenue per student of about $30,000 over an average tenure of five years. Before he even started in his new position he began to develop the framework of a new strategic plan. “This was much more about making smart investments than about continuing to cut,” he explained. “I told the board, ‘We’re losing money. We need to spend on programs that signal strength.’” The board agreed, and he presented his ideas to faculty and staff just before the start of the 2013–14 year. “We engaged in a conversation about how we characterize what we’re good at, what should our branding look like. I think I had like a 45-minute timeslot. But we ended up talking for two and a half hours.” At the end, they gave him a standing ovation.

Forward Momentum

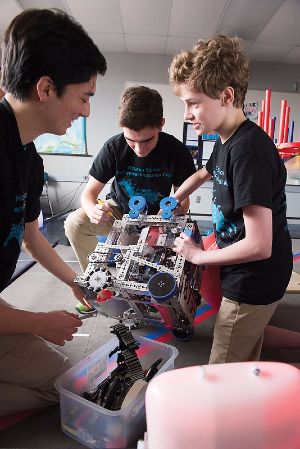

Saxenian’s first two years at McLean School brought a flurry of initiatives. These included market research and rebranding, a technology overhaul (and subsequent professional development), rolling out innovative new programs involving mindfulness, robotics and gardening, and upgrading the facilities in relatively modest ways, from reconceiving a traditional library as a learning commons to replacing the carpet in classrooms. Collectively, he said, “they created a positive environment and sense of momentum.”

Market research began first. Saxenian hired a company called Simpson Scarborough, whose typical clients are in higher education but whose president has an affinity for McLean’s mission. “She was excited about working with us, and their research helped us understand how the market perceived what we did well,” he said. This reinforced the issues with brand confusion, underscoring “the need to convey the fact that we could support students with learning differences without creating a stigma around them,” he said. A small marketing firm called GCF, for Greatest Creative Factor, developed the bold blue and orange logo and visual identity, but “actually we came up with the ‘transformative’ tagline.”

A technology audit took place in Saxenian’s first fall on campus. “It was soup-to-nuts,” he said, led by a company called Educational Collaborators whose consultants generally have full-time ed-tech jobs in other schools. Recommendations included replacing McLean’s network and servers, upgrading classroom technology, integrating the revamped library with the technology platform, and moving to an Apple platform including a 1-to-1 program for K–8 students and teachers. None was cheap, but it all supported Saxenian’s goal of investing in programs that would strengthen the school. “The Apple platform cost us more than a Windows platform, but as a former business officer I knew that if it brought us just a few more students it would pay for itself,” he said.

More importantly, said Saxenian, “We did a huge amount of training for teachers. We never want technology for technology’s sake. We want tools for collaboration, organization, creativity, research. We want our teachers to talk with each other about how to deploy their tools more effectively, and all of our teaching approaches are research-based.”

At Summit School, construction and other improvements across the 28-acre campus were already underway when Ebeling arrived in 2008, thanks to locked-in bond financing secured by the previous head and board. So even during those turbulent initial years, and even while realigning the school’s divisions and making other significant changes, he set his compass to Futrell’s “true north,” as crystallized in the tagline Inspiring Learning. “You can talk about your school until you’re blue in the face, but it really comes down to the students’ experience and what they tell their parents,” he said. Quoting a mantra known campus-wide, he added, “The single biggest variable in a student’s success is the quality of the classroom teacher as expressed in the student’s experience of the program. And the single biggest variable in the quality of a teacher is their professional development.”

Enter Summit School’s Center for Excellence and Innovation, or CEI. Through workshops, conferences and partnerships with other organizations, “The CEI is how we attract, develop and inspire our teachers,” Ebeling said. It began as an idea in the school’s 2011–2016 Strategic Plan, to “formalize leadership opportunities for faculty in the area of curriculum design, pedagogy and program development.” His view “is that everybody on this campus is an educator, and everybody is a student.” And since it’s not always financially feasible to send people away for PD, today the CEI hosts dozens of workshops and classes each year, on everything from mindfulness training for educators to understanding dyslexia for pediatricians. Summit faculty are the primary presenters; attendees come from the school and a variety of other institutions.

The CEI has become a revenue source since its launch, through registration fees and rentals. But revenue “wasn’t its original intent,” said Ebeling. As with everything at Summit School, mission comes first. “It comes back to the competition. Who are you in your market, and how do you convey that? I would argue it’s about sharing the rich, accurate narrative of who your community is. We do that. And we’re always growing. We’ll be better tomorrow than now.”

Leah Thayer is the editor of Net Assets and NBOA’s vice president of communications.

Download a PDF of the article.