|

Independent schools are wooing an increasingly small portion of American families. Only 9 percent of American families earn enough to afford the average independent school tuition, and that includes all families – not just those with school-aged children, explained Mitchell. Of families accepted into independent schools but choose not to attend, 45 percent said the choice was unaffordable, according to a 2016-17 EMA survey.

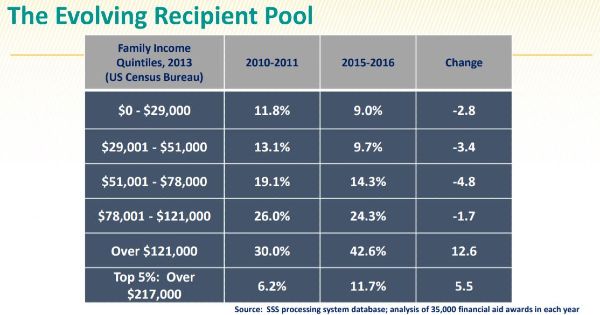

This means that financial aid, once reserved to enable students from lower income households to attend independent schools, is increasingly going to upper-income households. In 2010, about 12 percent of financial aid went to households in the lowest-earning quintile (20 percent), whereas in 2016, only 9 percent of aid went to that group. In contrast, the portion of aid-receiving families in the top 5 percent of earnings has doubled, from 6 percent in 2010 to 12 percent in 2016.

Following the 2008 recession, “one of the major concerns for schools was whether or not they could be financially sustainable by awarding too many large high-need grants,” said Mitchell. For example, a school might choose between spreading $20,000 of aid among five higher-income families and generate net revenue, or give $20,000 to one lower-income family, with much less net, he explained. The data show that independent schools are trending toward the former option.

With this shift has come a change in how schools refer to financial aid and the processes of awarding it. Renaming financial aid “flexible tuition, “indexed tuition,” “sliding-scale tuition” or something else is meant to bring more families into the application process, but it has had mixed results, said Mitchell. In some markets, changes bring in more higher-earning families, but in others it brings in more lower-earning families. “You have to make sure you do enough research to know that [rebranding financial aid will] make the difference in the right way,” he explained.

While shifting the distribution of financial aid may boost a school’s bottom line in the face of real financial pressures, it has also led to a widening gap between goals for aid and actual uses of it. In a 2016 survey, 58 percent of schools said increasing access was a very important goal of their aid program, but only 21 percent thought they were able to improve access through aid very well. And among financial aid professionals, fewer feel the words “compassion” and “satisfaction” describe their work, said Mitchell.

One positive trend is that more need is being met; whereas financial aid administrators reported their schools were able to meet an average of 66 percent of need in 2010, that jumped to 77 percent in 2016. And more financial aid administrators feel their work has a great impact on their school, rising from 65 percent in 2010 to 68 percent in 2016.

For much more on the state of financial aid in independent schools, watch the webinar, download the slides, read the transcript — and read the November/December Net Assets cover story, “Overcommitted: the Future of Financial Aid.”