Article by Daniela Holt Voith, Voith & Mactavish Architects

Independent schools across the country are experiencing the financial and operational impacts related to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. If your school had been planning to implement capital improvements prior to the pandemic, you may be wondering whether now is still the right time to do so — and, more importantly, what tools you can use to help you make that decision.

Most schools are familiar with both comprehensive campus-wide planning efforts and design/construction aspects of campus improvements. The former typically involves taking a big picture look at a school’s campus in the context of identifying programmatic needs and setting long-term goals, which often leads to identifying individual projects that then proceed into full design, documentation and construction. A lesser-known process lies somewhere in the middle and could be the answer many schools are looking for right now: the feasibility study.

The scope of a feasibility study is structured so that the school contracts for clearly defined services that produces only the information they actually need, often delivered within a few short months.

As the name implies, a feasibility study is intended to help determine whether a given project is feasible by producing just enough design work to allow your school to make an informed decision about pursuing, modifying or postponing a project. Rather than engage a full design team to document the project in its entirety, which often represents a significant investment of both time and resources, the scope of a feasibility study is structured so that the school contracts for clearly defined services that produces only the information they actually need, often delivered within a few short months.

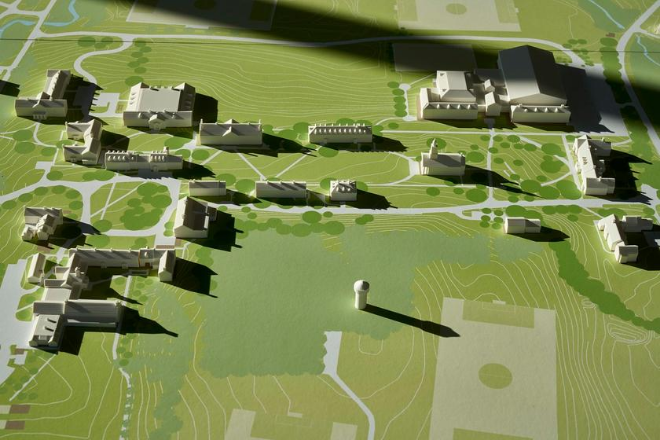

The architect will develop a conceptual design at a level that equates to approximately halfway through the schematic design phase of documentation. This can include a programmatic floor plan that shows where individual spaces are likely to be located, a massing model that shows how any new construction will look in its campus context, and perhaps elevations that illustrate where windows and doors will be positioned. Depending on the project, consultants like structural or mechanical engineers may be engaged to produce narrative reports that describe their expected scope. A civil engineer, preferably one familiar with the school’s specific municipality, can also be called upon if needed to advise on potential land use issues in a similar fashion.

Taken together, this information is enough for a third-party cost estimator to produce a reasonably accurate preliminary project budget. With a clear understanding of the conceptual design, possible zoning hurdles and cost implications, schools can then decide whether to proceed immediately based on the established scope; to modify the scope so that it is better aligned with what they are able to fund; or to postpone the project until available funds will meet what the project requires. The results can also be used to solicit board member feedback or to begin engaging potential donors.

With a reduced overall cost, the school was able to proceed through the design and construction phases and open the performing arts center a few years later.

For example, in 2012, an independent school in the Mid-Atlantic region had commissioned a feasibility study to evaluate whether their existing gymnasium could be converted into a new arts center. This study resulted in a conceptual design, structural and other narratives, and recommendations from a specialized theater consultant. Unfortunately, the cost estimate was far above what the school could invest in the project. The following year, our firm was engaged to conduct a second feasibility study and developed a concept that worked more closely with the existing structure and aligned with the school’s goals. With a reduced overall cost, the school was able to proceed through the design and construction phases and open the performing arts center a few years later.

Schools pursuing particularly large projects may also take a phasing approach, which allows the project to proceed in achievable “chunks” rather than move forward all at once. While the design work itself will typically remain relevant for several years, it is a good idea to get an updated cost estimate on the design concept if the study has not been implemented within two years, as local construction market conditions can be subject to change.

For most feasibility studies, the procurement process will be the same as it is for a regular design project. The school will either engage an architect with whom they have already established a relationship or select a group of pre-qualified firms and issue a competitive RFP. The proposal structure will likely be a single lump sum fee with any additional reimbursable expenses, like travel or document reproduction, clearly spelled out. It is always okay to ask for further clarification if you are unclear. Contractually, the Architectural Institute of America (AIA) offers the B203-2017 Standard Form of Architect’s Services: Site Evaluation and Project Feasibility, which can be an excellent jumping off point for negotiating the final owner/architect agreement.

Given the events of 2020 thus far, it is unclear how those projects and many others will proceed, but with the relevant information in hand, schools can be confident in their ability to make an informed decision and perhaps pursue pressing projects they might otherwise shelve for longer periods of time.